In 20th century American culture, the idea of zombies has traditionally been portrayed almost exclusively through the medium of film. The prototype for early zombie movies was White Zombie (1932), which took its subject matter directly from the zombie myths of Hatian folklore. White Zombie, one of the celibrated horror films of the “Universal era” (which also included important versions of Dracula, Frankenstein, The Wolfman and The Mummy) tarred Bela Lugosi as a rich

Haitian businessman who had taken upon himself to win the hand of a lady by turning her husband into a zombie. He had hoped that, by doing this, he would be able to rid her of her connection to her husband and thus clear the way for she and his romantic union.

Other zombie movies of the 30s and 40s followed suit insofar as they generally portrayed zombies as they existed in Haitian folklore: as beings whose brains had been zapped by some “master” who was then able to control their actions. Many of these pictures, such as The Voodoo Man (1944) and I Walked With a Zombie (1943) maintained that zombies were directly rooted, geographically and thematically, in Haitian myth. Other films, such as Revolt of the Zombies (1936) and Zombies on Broadway (1945) kept the theme but altered the geographic location. Also, while some of these films reinforced the idea that zombies were, in fact, the reanimated dead, some films portrayed zombies as being the products of a sort of malevolent hypnosis. In such films, the monsters were not “dead” at all, but merely humans who were reduced to a trance-like state and who were, again, controlled by a “master.”

During the “Hammer Films era” of the 1950s and 1960s, zombies began to a adopt a more sinister air. Films such as I Eat Your Skin (1961) and The Plague of the Zombies (1965) offered zombies that were forced to maintain their posthumous existence by actually consuming human flesh. This version of the zombie was generally still “controlled” by a “master,” but was awakened from its deathly state by some sort of supernatural or otherwise extraordinary force (satanic incantation, etc.). Here we see the invention of the “zombie-as-cannibal” type that was to characterize the genre for years to come. Virtually any given zombie from one of these movies was little more than “an utter cretin, a vampire with a lobotomy.” (Twitchell, 265).

combination of zombie, werewolf and vampire. they exist in a nether world between life and death like zombies, they devour like werewolves and they communicate their “disease” by biting like vampires.” (Paul, 263). The zombies in Night.. were weaklings, frail corpses whose only strength was in numbers. They posessed no supernatural abilities other than the fact that they were reanimated (Night.. is also unique in that it provides a scientific explanation for the return of the corpses–“radiation from a crashed spacecraft”). The zombies in Night.. exhibited physical weaknesses that were parallel to those of humans because they were merely humans, or at least the animated shells of humans. Night.. acknowledged that the enemy was us and us only, not some “other” or tyrannical force from beyond. It was, in essence, complete apocalypse that, unlike the “atomic mutant” movies of the previous decade, was rooted solely in humanity.

Night of the Living Dead also succeeded in shattering taboos of family and personal relations that had, until that time, been left untouched by American culture. Upon transformation into zombies, the characters in the film exhibited no moral responsibility at all, thus allowing them to take part in such ghastly activity as incest, cannibalism and paricide. Indeed, the film showed (zombie)

brother devouring sister and (zombie)

daughter devouring mother and father. This is nothing to say of the fact that all of the film’s characters, including the obviously heroic protagonist, die in the end, thus reinforcing the film’s depiction of all humans as flawed and vulnerable.

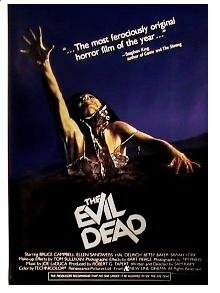

Zombie films after Night of the Living Dead basically followed in its footsteps. Indeed, many films, such as Romero’s own sequels Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985), as well as Zombie (1979) and Return of the Living Dead (1985) etc., were essentially carbon copies of Romero’s masterpiece, complete with overflowing cemetaries and strolling corpses hungry for human flesh. Many of these, such as Evil Dead 2 (1988) and Return of the Living Dead 2 (1988), shared Night..’s challenge of societal taboos. In fact, by this time, such activity had become the cinematic norm and no longer seemed shocking even. Truly, to see a zombie attack his mother or sink his teeth

into his sister had become common, even cliche, material for horror films. Indeed, by the time that Michael Jackson’s celebrated “Thriller” (see image to the left) arrived on MTV in 1984, zombies of the Romero variety had become safe for the whole family, even though, ironically, it was exactly that family that those zombies sought to destroy.

As is the case with the rest of the monsters listed on this site, there are certain symbolic implications tied up in the idea of zombies. In American culture, specifically within the medium of film, the zombie represents severeal different “fears.”

Zombies of the Haitian Voodoo variety represent a loss of cognition/ consciousness and also a loss of free will. What is it except these things, after all, that seperates us from animals. By “controlling” another person and eliminating that persons ability to make choices, let alone engage in conscious thought, the “controller” has reduced that person to the level of an animal and has robbed him of his humanity. A distinct parallel might be drawn here between cultures that have promoted the use of slavery (such as our own) and zombie films. To fear the possibility of zombies, then, is to fear enslavement.

Considering that zombies of the reanimated variety are nothing more than moving corpses, they come to embody the human fear of our own dead tissue. We, as humans, go to great lengths to obscure the remains of our dead, especially our loved ones. If someone we know dies, our mental image of that person stops at the grave.When we build a picture in our mind’s eye of that person, it is not the rotting corpse or skeletal remains that we see–even though that is the person’s current status–but the memory of that persons conscious life. It is no mistake that we bury our corpses “six feet under” so as to eradicate the ugliness of decomposition.

Therefore, to confront a zombie is to be reminded of our own mortality. It, as is proven in Night of the Living Dead and its ilk, is especially terrifying to encounter, let alone be attacked by, the physical image of one’s deceased beloved. Being that our mortality is something that we try to decorate with tidy rituals and outright denial, zombies serve as a painfully striking reminder that we will all eventually return to the same stinking earthly essence from which we are born.

Night of the Living Dead and its counterparts also illustrate the fear of widespread apocalyptic destruction. It is not a coincidence that these movies appeared mostly at the height of the Cold War paranoia that was taking place earlier this century. Much like the atomic bomb, zombies are unleashed in a chain reaction, each devoured corpse arising and looking for more human flesh to consume. As the zombie count increases exponentially, they cover more and more distance until they overtake massive amounts of land area. Indeed, by the end of Romero’s Day of the Dead (1985), the final installment of his “Dead” trilogy, only a small militia-esque band of survivors is remaining in the United States. Consequently, they choose to relocate to an uninhabited island in the tropics as the U.S. becomes a barron wasteland, populated only by the walking dead. At the conclusion of Return of the Living Dead (1985), the U.S. government chooses simply to erase the area populated by zombies with a nuclear missle (ironically, the process of human reanimation was enacted by nuclear radiation to begin with and thus, in this reciprocity of events, not only is the fear of holocaust represented, but also the metaphorical enactment of full-on nuclear war).

Zombies also represent widespread annihalation in the form of plague-like sickness. The implications here are basically the same as they are with nuclear apocalypse, but on a more personal and intimate level. Romeroesque zombies multiply by infecting their victims through the mixing of bodily fluids (saliva, etc.). When a person is attacked by a zombie, that person, in a process similar to that enacted by vampires, becomes a member of the “undead.” As is the case with the cold war similarities, the fact that the majority of the Night..-style zombie movies arrived during the 80s during the height of the AIDS epidemic is difficult to overlook.